The following film lists are admittedly compromised somewhat by the limitations of the cinematic experience and personal prejudices of the reviewer, and no such list could obviously ever hope to be comprehensive or definitive enough to suit all tastes.

It is also less comprehensive than it might otherwise have been as I have obviously had to avoid incorporating some otherwise excellent but unheralded films by reputation that I have not seen personally. That being said, many of these listed below I viewed more than 20, or even 30 years ago, and so quite possibly I may have a different critique of them in the cold light of day if they were reviewed again today.

Some of these films are quite difficult to source on DVD in Australia at least, or are even unavailable entirely, while some have perhaps had solid critical support but have had limited commercial exposure or else little mainstream appreciation. A few, possibly contentious inclusions on the list were once well known and respected or even popular in their day, but have been included because I feel they are at risk of being forgotten by the mainstream due to their subject matter, or perhaps their idiosyncratic approach or viewpoint.

I hope that this list might also trigger some readers to investigate some of these more obscure gems, and perhaps even to compile lists or suggestions of their own.

- The Academy of the Under-rated-

(Undiscovered , Underappreciated or Under-exposed Films)

Badlands,

Director Terence Malick’s remarkable first feature is a masterpiece, only very loosely based on the Starkweather-Fugate killing spree in the 1950’s, being one of the best and most important films of the 1970’s. It is especially notable for the exceptional performances elicited from the two lead actors- with Martin Sheen chillingly effective as the psychopathic killer Kit Carruthers, but also an as yet unheralded Sissy Spacek (in only her second film) as his amoral yet childlike accomplice Holly. Holly’s detached and blasé voice over monologue stands in stark counterpoint to the brutality of the actions taking place at her boyfriend’s hand, delivered in a mixture of romanticised, fantasy clichés and girlish naiveté.

Malick importantly refuses to make the viewer complicit in his depiction of scenes of wanton murder, minimising even the slightest hint of glorifying the violence that is portrayed with subtlety and a minimum of voyeurism, setting it apart from other films within the genre. His direction is incredibly assured yet understated, and never less than note perfect, with the brilliant use of incidental music combined with Tak Fujimoto’s excellent cinematography capturing the era to perfection, showing the stark desolation of the wilds of South Dakota that effectively mirrors the characters’ complete lack of emotion and empathy for their victims. A compelling and thought-provoking film.

Mountains of the Moon,

Bob Rafelson’s tour de force retelling of the discovery of the source of the Nile, focussing on the ensuing conflict between two renowned African explorers, the upright and aristocratic John Hanning Speke and the wholly unconventional libertine, Sir Richard Francis Burton.

It’s the depiction of Burton, one of the most enigmatic, erudite, controversial and courageous rogues in the annals of English history, combined with the depiction of the sundry perils of the golden age of Victorian exploration, that ultimately makes this absorbing film an extremely satisfying and often exhilarating experience to savour.

Wise Blood,

John Huston’s jet-black comedy is based on Flannery O’Connor’s searing dissertation of the mindset of the American South generally, and darkly satirical take on evangelical fanaticism in particular.

Hazel Motes, as played brilliantly by a spell-binding Brad Dourif, tries to establish a “Church of Christ Without Christ”, before spiralling out of control in a descent into nihilistic obsession and angst-ridden blindness that is by turns sardonically humorous, fascinatingly bizarre and chillingly tragic. Whilst not for all tastes, it is a richly rewarding experience for patient viewers.

Cutter’s Way (1981),

Czech émigré director Ivan Passer fashioned a compelling film noir homage in this barely released, vastly under-rated and under-appreciated gem that, among other things, explores the seamy underbelly of drugs, prostitution and murder in a Californian beachside community.

A shiftless playboy and drifter (Richard Bone) and a crippled Vietnam veteran (Alex Cutter) become entwined in the brutal rape and murder of a teenage girl, when the pair become convinced that it may (or may not) have been committed by J.J.Cord, a wealthy and powerful local oil baron. The duo embark on a quest to prove his “guilt”, and perhaps extract some “justice” for his privileged existence, a high life perceived by them both to be at the expense of others.

The performances are uniformly excellent, with the deranged Cutter as played with a manic intensity by John Heard (never better in a cross between Don Quixote and Captain Ahab), with a laconic and understated Jeff Bridges as Bone, and especially in the moving performance by Lisa Eichorn as Cutter’s long suffering and terminally depressed wife Mo.

The film has touches of surrealism blended with splashes of irony and astute observational humour that render the film to be an intimate portrayal of the meaning of love, death, pain and loss at the core of a largely amoral and soulless modern American society.

Nineteen Eighty-Four (1984),

George Orwell’s brilliant and prescient novel, “1984”, is given a superlative treatment by Michael Radford, with brilliant, note-perfect performances by John Hurt as Winston Smith, and Richard Burton in his final role as the villainous O’Brien.

The bleakness of the novel is rendered in unrelenting, but entirely appropriate detail as a stark depiction of the ultimate totalitarian nightmare. The last flames of humanity and rebellion in worker-drone Winston are quashed with ruthless efficiency by the State, when confronted by the craggy, world weary face and mellifluous yet strangely mono-tonal voice of Burton’s O’Brien as the dispassionate agent of institutionalised inquisition and torture.

“Big Brother” and it’s all-seeing eye has invaded every corner of Oceania’s rubble-strewn streets and dilapidated apartment blocks, while the populace indulge in “Two-minute Hate” sessions, hurling abuse at Goldstein and other enemies of the State. And the price of love? – Room 101!

Thieves Like Us,

Director Robert Altman’s remake of “They Live By Night” is one of his most fully realised and best films, an under-appreciated Depression era story about fugitive bank robbers, who set out on a crime spree which is ultimately doomed to failure.

In contrast to the usual mythologizing and violence of such films, Altman subverts the usual conventions of the genre and focusses instead upon the simplistic love story between two of the fugitives, which is both tender and touchingly played out.

Great attention is paid to such details as the 1930’s era radio programs heard playing in the background which act as an oblique commentary on the action, while the ubiquitous Coca-Cola consumerism highlights the aimless pursuit of the American Dream by these misguided outcasts of society.

The Day of the Locust,

John Schlesinger’s searing and incisive portrait of the seamy side of 1930’s Hollywood society, is portrayed with unerring accuracy in this adaptation of Nathaniel West’s classic novel.

The downbeat treatment and confronting subject matter cannot dim the brilliance of this darkly comedic satire, with Karen Black’s standout performance and excellent supporting cast deserving of a far wider audience for their toil than it’s initial run at the box office ultimately received.

Rarely has “old Hollywood” been so authentically and trenchantly observed, and with such clarity and biting cynicism, with the exception of course of the luminous and iconic cinema milestone “Sunset Boulevard”.

Mishima: A Life in Four Chapters,

The life of renowned Japanese author, Yukio Mishima, is brilliantly depicted in this uniquely framed film by Paul Schrader. In a project of great personal importance to the director, better known as author of “The Yakuza” and Martin Scorcese’s “Taxi Driver”, Schrader handles the complex subject of this idiosyncratic literary icon intelligently and with taste, sensitivity and sophistication.

Schrader cleverly interweaves past and contemporary (c. 1970) biographical elements with stylized dramatizations of three of his novels, “The Temple of the Golden Pavilion”, “Kyoko’s House” and “Runaway Horses”. By integrating his artistic expression with events and incidents in Mishima’s life, we are given insight into the controversial author’s obsessions and inherent contradictions.

The film is divided into four chapters, “Beauty”, “Art”, “Action” and “Harmony of Pen and Sword”, encompassing Mishima’s attitudes and the beliefs that motivated him most prominently throughout his incredibly prolific, influential and richly varied life. Mishima rejected post-war Japan’s inexorable movement away from its core traditions and rituals through embracing Western ideas and culture. He believed this would inevitably lead to the abandonment of adherence to strict codes of honour that he felt defined the Japanese psyche, and so as a consequence Mishima formed his own private army (the Shield Society) ostensibly to safeguard these traditions. He eventually planned a coup d’etat to restore Japan to Imperial rule, but with its failure, Mishima committed public Seppuku at age 45.

Brilliant photography by John Bailey adds immeasurably to the film by capturing Mishima’s past, his last days, and his artistic imagination in three stylistically distinct ways. The film is greatly enhanced by a memorable Phillip Glass score melded perfectly to the action, while Eiko Ishioka’s distinctive and flavourful production designs provide a vivid depiction of his various literary works.

A truly unique film, which deserved far greater box office and critical success than it garnered when first released, it is one of the best explorations of the nature of the artist and his role in society.

Lacombe Lucien,

In a small French village in 1944, an unsophisticated and highly impressionable teenager is rejected by the resistance because of his youth and immaturity. Instead, through a chain of circumstances, he becomes a collaborator with the German occupiers, acting as their brutal enforcer having taken on the Gestapo thug persona almost by osmosis, rather than out of any antisemitism or ideological inclination on his part.

Lucien (played with great authenticity by the ill-fated Pierre Blaise) is offered some chance of redemption through his involvement with a Jewish family, and especially in his relationship with their daughter, France (Aurore Clement), that puts him tentatively on the path to something akin to self-awareness.

Director Louis Malle based much of this controversial film upon his own personal wartime experiences, and the themes of the banality of evil and the arrogance and naivety of youth are eloquently and masterfully expressed through actions of the title character.

One of the best and most compelling portraits of life under the reign of the Nazis in Vichy France during WW2.

One Hour Photo,

Mark Romanek’s disturbing and subtle psychological thriller stars Robin Williams in possibly his best dramatic performance as Si Parrish, a seemingly innocuous, non-descript and socially awkward photo-developer – “Si, the Photo Guy”.

Behind this insignificant, milquetoast exterior lies a disturbed obsessive who has become pathologically fascinated by a particular family who regularly frequent his store over a period of years. He spends his nights fixating on this family’s photographs, fantasising about being an integral part of their family unit, until his delusional beliefs lead him to try to insinuate himself directly into their lives.

The film is aided greatly by the director/writer’s tendency to eschew the violent, stereotypical approach of the usual Hollywood fare, in favour of concentrating on the psychopathology of this man’s loneliness, despair and longing for a normative existence which is completely out of his reach. Photography allows this damaged soul to simulate the life he desires, but ultimately it is only a facsimile of life, and this will eventually give way to a desire for more tangible and real experiences.

That the viewer comes to care somewhat for this man teetering on the brink of madness is but one of the strengths of this quiet, slow-burning thriller.

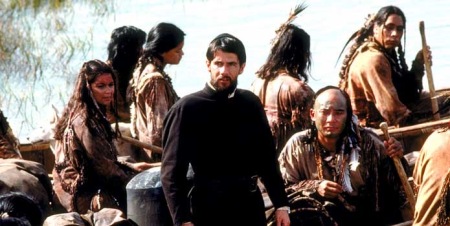

Black Robe,

Australian director Bruce Beresford has fashioned a compelling treatise on religious faith and the hardships one must endure when pursuing a spiritual quest. It depicts the collision of European and Native American cultures that inevitably occurred soon after first contact.

Set in 1634, the film begins in the only European settlement in early New France, in what will later become Quebec City, where a newly arrived Jesuit priest (Father LaForgue, brilliantly played by Lothaire Bluteau) engages with friendly Algonquin natives who agree to take him 1500 miles up the St. Lawrence River, and then up its smaller tributaries and overland to reach a Huron native settlement. It is late fall, and winter is closing in, and along the way many hardships arise as Father LaForgue is attacked, imprisoned, and left alone on his ultimately futile quest.

The film is notable for by far the most realistic, brutally uncompromising and meticulously researched representations of indigenous life ever put on film. Notably, the film includes authentic dialogue in the Cree, Mohawk, and Algonquin languages. The French characters speak English in the film, whilst Latin is used for Catholic prayers. The film manages to refrain from easy, judgmental or stereotypical renderings of either the religious missionary himself, or the various natives (both friend or adversary) whom he encounters on his arduous journey.

King of Comedy,

Dismissed by critics on its initial release in 1983, and a rare box office failure for its director Martin Scorcese, this cynical and ultimately chilling satire is in many ways a companion piece to Scorcese’s previous, hugely successful foray into psychopathology, in the celebrated film “Taxi Driver”.

This jet black comedy skewers our obsession with fame and celebrity in its portrait of Rupert Pupkin, the would be stand up comic who lives in a fantasy world in his parents’ basement, and his dream of performing on the Jerry Langford Show as his pathway to much a dreamed of career as a comedic superstar.

Robert De Niro as the delusional, fame obsessed and yet at times strangely even endearing Pupkin, delivers what may be his finest performance in films, immersing himself almost completely in this complex character who evinces feelings of sympathy, revulsion and dread by turn as the plot unfolds.

Jerry Lewis, playing against his usual type as the Johnny Carson-like talk show host Jerry Langford, is a brilliant piece of casting in a serious role, playing the business-like and somewhat abrupt established star who at first humours Pupkin, only to find this segues into unwanted intrusion into his cloistered private life, and ultimately to his kidnapping.

The Jerry Langford character is every bit as sad and pathetic as his alter ego Rupert Pupkin, or his accomplice Masha (Sandra Bernhard) the obsessed fan who assists in the kidnapping for perversely sexual motives. Langford is bored by the trappings of his fame, and has long since become a captive in his own home, unable to walk the streets without being accosted, and unable to form meaningful relationships as those around him are only interested in what they can get out of him. He is paying the highest possible price for the fame that Pupkin actively (and ironically) seeks, but is ultimately an isolated individual living under siege in his own life, even before these deluded and dangerous psychopaths invade his life, turning it upside down.

That the film manages to be both darkly comic, but also deeply tragic at the same time, makes this a film of rare insight and one which has become increasingly more relevant, and unerringly accurate as time has gone on.

Fat City,

John Huston’s 1972 boxing film is a true sleeper film from the legendary director who had rebounded after a string of less than worthy films that preceded it.

Starring Stacy Keach, in his best ever film role as a washed up boxer (Bill Tully), who trying to get back in shape at the gym for one last crack at the “big time”, when he spars with an up and coming 18 year old (played by Jeff Bridges), whose potential as a boxer rekindles Tully’s enthusiasm for one last comeback.

The film’s portrayal of desperate people grasping in utter futility at the mirage of a successful existence is as unsentimental as it is brutally honest, whilst the skid row milieu of Stockton, California has been captured in all its squalor and depravity by the sharp camera work of Conrad Hall. Nicholas Colasanto, as Tully’s coach Ruben, is another standout performer amongst a terrific ensemble cast.

A rare gem of a film that strikes at the desperate fringes of society with unerring accuracy and poignancy.

The Big Red One (The Reconstruction),

Samuel Fuller’s own war experiences in WW2 with the First Infantry Division (“The Big Red One” of the title) served as the inspiration for this poignant treatise on the futility and brutality of war.

The film focusses on a core group of four soldiers (the “Four Horsemen”, a composite of his own wartime comrades) who survive while other anonymous, inexperienced replacements come and go to their deaths.

Told through a series of startling vignettes across various disparate theatres of conflict, the pervading mood fluctuates wildly from intense fear and tragedy on the one hand, to gallows humour, absurdity and disbelief at the other extreme.

As Fuller opined, “the real glory of war is survival”.

The Duellists,

Ridley Scott’s debut film, from the Joseph Conrad story “The Duel”, details an obsessive feud between two officers in the 7th Hussars Regiment during the Napoleonic wars.

It deals with its themes of honour, obsession and violence through a series of meticulously staged and choreographed duels between the protagonists, who represent different classes (D’Hubert the aristocrat, Ferault the commoner) and demonstrate wildly different temperaments, lying at the heart of their intense rivalry.

These duels and the conflict between the two adversaries are set against a backdrop of early 1800’s France and the rise and fall of Napoleon, with painterly images and impeccable production design adding immeasurably to the film’s sense of time and place.

Repulsion,

Roman Polanski’s examination of the fragile mind of Catherine Deneuve’s character, Carol Ledoux, left alone by her sister to fend for herself while away on holiday with her boyfriend.

Carol is beautiful in a very fragile way, obsessive-compulsive but also unusually shy, and a somewhat detached and aloof young woman. Left alone in the apartment, she descends into a nightmare world of hallucination, fear, sexual repression and ultimately catatonic madness.

The horror of her distorted imagination is chilling and effectively evinced, with Deneuve brilliantly capturing the young waif whose mind is shattering before our eyes.

Repulsion is an unique and masterful horror film, which subtly uses camera techniques and musical motifs to document the claustrophobia, paranoia and the nightmarish insanity visited upon this damaged young woman in her tragic decline.

Peeping Tom,

Michael Powell (Life and Death of Col. Blimp, Black Narcissus, The Red Shoes), along with partner Emric Pressburger, was a genuine cinematic master of 1940’s British film, but effectively his career and reputation was ruined by the savage response to this misunderstood film.

It portrays the pathetic life of a sexually depraved and voyeuristic murderer, played with nervous intensity by Carl Boehm. He lures and then murders prostitutes with the sharp point of his camera tripod, and is obsessed with filming these women while he murders them, replaying the films capturing them at the point of death over again for his sexual gratification.

Not only does the director comment on the nature of sexual violence, but with the constant point of view shots used to great effect, he also obliquely refers to the voyeuristic nature of film violence. Thereby, Powell draws uncomfortable parallels with the vicarious pleasures experienced by filmgoers in their collective fascination with lurid depictions of violence in cinema itself.

Powell’s trademark attention to detail, production design and mise en scene is characteristically excellent, but unfortunately the unpalatable message and the subject matter were too confronting for the audiences of the day.

A sad end to a brilliant career for a true genius of British cinema.

Tucker: A Man and His Dream,

Francis Ford Coppola’s homage to inventor/con man Preston Tucker, who attempted to take on the “Big Three” auto makers with his own revolutionary vehicle- the “Tucker Torpedo”, billed as “The Car of Tomorrow- Today!”

With a style reminiscent of 1940’s advertising art, the picture is infused with a disarming optimism and boundless enthusiasm in its portrayal of this creative but flawed individual, with darker undertones bubbling to the surface as his dreams are crushed by the collusion of his competitors and government, who are prepared to go to any lengths to stifle any opposition.

A highly technically proficient film with a wonderful visual sensibility in its presentation, this film was a dream project of the director, who clearly identified with the daring, determination and innovation of his protagonist.

Hope and Glory,

John Boorman’s reminiscences of wartime England provide a vivid portrayal of life during “the Blitz”, giving a child’s eye view of growing up and attempting to maintain a sense of normalcy while all around lies destruction, ruin and dislocation.

Drawing extensively from the director’s own experiences, the near plotlessness of the film is actually its most apparent strength, never seeming less than true in its depiction of events, transporting the viewer to a time and place in history with subtlety, honesty and clarity.

Fearless,

Jeff Bridges stars as a plane crash survivor, whose fear of flying belies his response to the tragedy, calmly guiding survivors to safety, then subsequently failing to cope with the ensuing emotions that occur in its aftermath.

With the realisation of having come so close to death, he fails to exhibit the expected responses in recognition of his heroism, nor in receiving a second chance at life. Instead, he becomes completely detached from and even resentful toward his wife and family, and notably seeks solace for his alienation in a fellow survivor, and more troublingly by confronting danger with a series of reckless behaviours which suggest compulsive need to challenge and master his fears.

His pathological response to his trauma and his survivor’s guilt is subtly invoked due to the sure hand of director Peter Weir, and a brilliant understated performance by Jeff Bridges in the lead role.

Sundays and Cybele (Les Dimanches de Ville d’Avray),

One of the most fondly remembered films of my adolescence. Director Serge Bourguignon fashioned a masterpiece from the tale of a shell-shocked soldier whose friendship and love for a twelve year old girl leads eventually to tragedy.

Featuring a wondrous performance from child actress Patricia Gozzi, as the 12 year old girl neglected by her parents and appearing wise beyond her years, who becomes a mother figure and even a platonic “lover” to the traumatised man.

The controversial nature of the subject matter of the film is tastefully and sensitively handled, with dazzling black and white cinematography and subtle use of music to set a dream-like atmosphere that lends an air of poetic unreality to proceedings.

Rather than some sort of apologia for paedophilia, the objective view point taken by the director encourages empathy for a damaged young man reverting to a childlike and vulnerable state because society has been oblivious to his plight, as well as for a young girl whose childhood is curtailed by the casual rejection of her parents.

It is to be duly noted that the Roman Goddess, “Cybele”, is an eternal Earth “mother” figure, who was renowned for having a eunuch priesthood as mendicant followers, thus emphasising the director’s implicit intention that the relationship between the soldier and the young girl be understood to be entirely innocent of any sexual undertones.

Crimes and Misdemeanours,

Woody Allen’s seriocomic film is a rich blend of drama, comedy and satire, revolving around two separate and outwardly disparate story lines which merge, albeit mainly thematically, as the film progresses.

The first thread involves an adulterous ophthalmologist (Martin Landau in an outstanding performance) who plots to murder his mistress to prevent her from compromising his privileged existence by informing his wife of the affair.

The second involves an unsuccessful filmmaker (Allen) who is simultaneously making a documentary on his much despised brother-in-law (a successful TV sitcom director played by Alan Alda) while also vying against him for the love of a film producer colleague (Mia Farrow).

The film is a meditation on morality and conscience, life and death, God and religion, crime and responsibility, love and lust, and the injustices one must endure in the sometimes fruitless pursuit of happiness.

All this is leavened with moments of high comedy and witty punchlines which act as a counterpoint the downbeat nature of the tragedy as it unfolds.

Ed Wood,

Tim Burton’s homage to the worst film-maker in history, whose legendary cinematic cult “gems”, such as “Glen or Glenda” and “Plan 9 from Outer Space”, redefined the meaning of “schlock cinema”.

Featuring a winning performance from Johnny Depp as the irrepressible and hyper-optimistic director, but overshadowed by a brilliant Martin Landau as his tragic, drug-addicted friend, Bela Lugosi.

The scenes showing the affection Depp’s character feels toward the pathetic, dying man are touching and give the black comedy elements a humanistic quality to counterbalance the array of quirky personalities and strange outcasts who inhabit Ed Wood’s circle of friends who are also “stars” of his films.

Instead of mocking his main character, Burton has a real affection for Wood’s enthusiasm and love of film, even while acknowledging his absolute rank failure as an artist, as well as the magnitude of his delusion as to his abilities.

Kwaidan,

Four Japanese Ghost stories, from the pen of expatriate American but naturalised Japanese citizen Lafcadio Hearn, are rendered brilliantly by genius director Masaki Kobayashi (The Human Condition, Harakiri, Samurai Rebellion).

Drawing extensively from Noh and Kabuki theatre traditions in its makeup, costumes and colour palette, Kobayashi also utilises Japanese acoustic instruments such as the biwa to chilling and flavourful effect.

The four separate yet vaguely connected stories are: “Hoichi the Earless” , “The Woman in the Snow”, “Black Hair” and “In a Cup of Tea”, with each rendered with superb colour composition and a stunningly unique visual, painterly style which adds such resonance and clarity to what may superficially at least seem to be slight supernatural tales.

Slow moving but utterly compelling, with some of the most magnificent widescreen cinematography in all of cinema, these stories transcend the limitations of the genre to attain such a high artistic level that it lingers in the memory long after viewing.

The Orphanage (El Orfanato),

A haunting Spanish gothic horror film, directed by Juan Antonio Bayona, which unfolds more like a fable, while delivering an intensely emotional and imaginative supernatural tale of lost innocence and maternal love.

A tour de force lead performance by Belen Rueda, a young woman who returns to the seaside orphanage where she grew up, with her husband and her terminally ill adopted son, Simon.

When the young boy disappears, the heartrending search is complicated increasingly by disturbing supernatural events which illuminate the dark past of the orphanage, while casting doubt upon the sanity and the resolve of the increasingly distraught and tormented mother in her quest to find her lost son.

The performances are uniformly excellent, while the rugged coastal setting, the isolated lighthouse and the architecture of the orphanage itself invoke an atmosphere of pervading dread and impending doom, adding immeasurably to the suspenseful and ultimately tragic story as it evolves with nuance and subtlety.

The Shadow of the Vampire,

Unheralded and idiosyncratic film with an intriguing premise, namely that Max Schreck, the star of F.W Murnau’s 1922 German silent classic film “Nosferatu”, was not an actor but was in fact himself a vampire.

Murnau’s pursuit of perfection in his masterpiece leads him to broker a deal, sacrificing his unwitting leading lady to the vampire’s bloodlust once filming is completed.

E.Elias Merhige fashions a wickedly left-field comedy from this conceit, with Willem Dafoe unrecognisable as the rat-like, disgusting creature of the night whose bizarre behaviour and depravity is a sight to behold.

John Malkovich as the inhumane, controlling and perfectionistic director (Murnau) is equally monstrous, prepared to sacrifice all at the altar of his artistic vision.

The satire is broad but effective and the film captures the mood and the look of German expressionist cinema beautifully.

Gods and Monsters,

Celebrated Hollywood director James Whale’s last days, before his mysterious death by drowning in his own swimming pool in 1957, are rendered in this semi-fictionalised account by director Bill Condon.

The film depicts the director of “Frankenstein”, “The Invisible Man”, “Waterloo Bridge” and “Journey’s End” when he is recovering from a stroke and is confronted by his loneliness, his loss of creativity and ultimately his own mortality.

The film focuses on his relationship and attempts to befriend a handsome gardener in his employ, played by Brendan Fraser, which has the potential to offer a form of redemption to both. Having been forgotten by his moviemaking peers and retreating into his private world, Ian McKellen as James Whale is cultured and eccentric, a tortured homosexual and an outcast who drifts between fantasy, memory and reality while manipulating those around him in true directorial style.

Excellent performances by the lead players with subtle links to Whale’s art in his film make this an absorbing character study with broader implications and interest.

The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford,

Elegiac meditation upon the mythic Old West, focusing upon 19 year old Robert Ford (Casey Affleck) and his relationship with an erratic and often mentally unbalanced “hero” in the outlaw Jesse James.

Director Andrew Dominick’s excellent adaptation of Ron Hansen’s novel, and Roger Deakins’ exceptional cinematography, capture the essence of the era that marked the last days of the James Gang.

The cult of personality that surrounds Jesse, played with admirable intensity by Brad Pitt, captivates then disillusions and finally enrages the young Ford, whose obsession with his hero eventually leads to the ultimate act of revenge and betrayal.

Although only 34 years old, James is in decline having already enjoyed the pinnacle of his fame, and now more content to settle into domesticity with wife and children, and increasingly paranoid and distrustful of the remnants of his once tight-knit gang.

A fine ensemble cast is uniformly excellent, adding dimension and emotive resonance to each of the characters, while the tone and mood recalls Terence Mallick’s brilliant “Days of Heaven” as a lyrical and haunting evocation of a bygone era.

Solaris (1972),

Andrei Tarkovsky’s answer to Stanley Kubrick’s “2001: A Space Odyssey” is based upon the novel by Stanislaw Lem.

It concerns the crew of a Space Station orbiting a distant, mysterious planet, Solaris, which has an apparent extracorporeal intelligence, and the ability to invade the consciousness of the cosmonauts by resurrecting their distant memories as well as people from their past lives and thereby distorting their sense of reality.

This provides Tarkovsky with the framework upon which to meditate on the nature of reality, of memory and of what it is that makes each one of us human, while also invoking a subtle commentary on the U.S.S.R. under Communist rule.

While it’s languid pace may not suit all tastes, Solaris is a truly original, intensely personal, frightening and thought-provoking masterpiece of Russian cinema which rewards patient and attentive viewers.

Matewan,

Independent filmmaker John Sayles’ low-key but effective drama is set in the coal-mining town of Matewan, West Virginia, in 1920.

The Stone Mountain Coal Company controls the lives of its workers through intimidation and draconian working conditions. The drama surrounds the rebellion of these workers that ends in violence and bloodshed, which is portrayed with sympathetic but dispassionate intensity.

Haskell Wexler’s cinematography, and uniformly excellent performances also contribute to making this low budget, independent film an American near-classic in the vein of “Grapes of Wrath” or “How Green Was My Valley”.

Citizen X,

This excellent HBO made-for-TV docudrama, based on the true story of a Russian serial killer, is one of the finest examples of the genre, precisely because it largely eschews the more gruesome forensic detail and graphic action in favour of a more comprehensive and insightful treatment of the events, its investigation and the historical and socio-political milieu in which the murders occurred.

Set in 1980’s and 90’s Russia under Communist rule, it tells the story of Andrei Chikatilo, The Ripper of Rostov (an excellent portrayal by Jeffrey DeMunn), who, over many years, claimed more than 50 victims, most of whom were under the age of 17. Police investigations were hampered by a stifling Soviet bureaucracy, institutionalised incompetence and by an unwillingness by those in power to acknowledge the possibility of such a perpetrator being prevalent within their society.

The story is told from the viewpoint of the dedicated detective in charge of the case, Lt. Viktor Burakov (played brilliantly by Stephan Rea), whose tenacity overcomes his inexperience as he evolves through the case in pursuit of the perpetrator.

Directed with a sure and steady hand by Chris Gerolmo, who is careful not to over sell the subject matter throughout, and the film is notable, amongst other things, for a series of fine performance that were elicited from such stalwarts as Donald Sutherland, Max von Sydow and Joss Ackland in the secondary and supporting roles.

The Right Stuff,

This 1983 film adaptation of Tom Wolfe’s highly regarded novel compares the experiences of the test pilots at Edward’s Airforce Base (engaged in high- speed and high altitude flight), to America’s first astronauts selected in Project Mercury, the program to undertake America’s first manned space missions.

Philip Kaufman’s flavourful, if somewhat fictionalised account captures the pilot’s spirit of adventure and the exhilaration of flight, while being redolent with interesting insights and perspectives into this fascinating era of early space exploration.

A fine ensemble cast is uniformly excellent in this 3 hour epic, which fairly accurately depicts the personalities involved while the backdrop of Cold War politics and the 1960’s American culture adds immensely to the interest and engagement of the story.

One note of criticism, however, is the rather inaccurate depiction and attribution of Gus Grissom’s mishap after splashdown with his mission, which unfairly lays the blame upon him personally. Subsequently, Grissom has been vindicated by time and an equipment malfunction was indeed deemed responsible for the incident depicted where explosive bolts on his escape hatch discharged prematurely.

Grissom’s subsequent death in a launch-pad fire in the early Apollo missions a few years later only serves to heighten the need to redress this particular injustice and its prospective damage to his otherwise spotless reputation..

Targets,

Made on a shoestring budget by first time director Peter Bogdanovich, this ‘B’ movie intertwines the story of ageing horror movie star, Byron Orlok, crossing paths with the seemingly ordinary, clean-cut quintessential American youth, Bobby Thompson, who embarks on a shooting spree after casually murdering his family.

Bogdanovich depicts 1960’s Southern Californian suburbia in all its boredom and banality, and the seeming ordinariness of this modern day “monster”, which is loosely based on the 1966 Charles Whitman sniper seige.

Thompson eventually is seen atop a Gas tower shooting at passing motorists, then ultimately at a Drive-In Cinema where he shoots repeatedly from the screen killing the unsuspecting viewers as they sit in their cars, whereupon he is eventually captured by Orlock in the denouement of the film.

The film’s muted and detached approach to the subject is highly effective in heightening the unease of the viewer, while the confrontation of the old-time classic horror icon with the modern, disaffected, nihilistic youth brings the film to a satisfying and thought-provokng conclusion.

An exploitation flick with a splash of social commentary, and a homage to classic cinema rolled into one, while also making a virtue out of its inexperienced director, low budget and various logistical constraints.

Colossus: The Forbin Project,

One of the most under-rated Science Fiction genre films, Joseph Sargent’s engrossing thriller combines thematic elements of Man versus Machine, Cold War brinkmanship and Doomsday prophesy.

Dr. Charles Forbin (Eric Braeden) creates a supercomputer, “Colossus”, for the Pentagon to control the West’s nuclear arsenal. Unbeknownst to them, the Russians have developed their own similar computer, “Guardian”, for much the same purpose.

When Colossus is given permission to “investigate” this other computer’s capability, the two computers unexpectedly combine into one all embracing system communicating between one another in their own language.

The computers decide on mankind’s behalf that for its own safety total control over all human activity must be given over to them, with the threat of nuclear strikes should any attempt be made to disrupt the link of the two systems.

A battle of wits ensues between Dr Forbin and his creation over the fate of mankind, its freedom and its self-determination.

In spite of somewhat dated technology, this is an intelligent Science Fiction film with much that still resonates with modern audiences, particularly in this era where the pitfalls of the “precautionary principle” are all too evident.

Walkabout,

Nicholas Roeg’s legendary visual flare and exceptional cinematographic skills are used to stunning effect in this intriguing film, set in outback Australia and featuring two schoolchildren stranded and left to fend for themselves in the desert after their father’s violent suicide.

Encountering an Aboriginal 16 year old on ‘walkabout’ provides an opportunity to delve into themes of modern civilization and technology versus an ancient culture, racial differences and communication between diverse cultures, survival in a hostile environment, and especially in childhood innocence and the rites of passage to the adult world.

Much of it is told idiosyncratically in the juxtaposition of visual images and with auditory cues, sometimes subtle, sometimes jarring for effect and on occasions perhaps somewhat over-elaborative.

That being said, this highly original and effective film will live long in the memory of the discerning viewer.

Don’t Look Now,

The drowning death of their only daughter has devastating effects on a married couple, played by Donald Sutherland and Julie Christie, in Nicholas Roeg’s disturbing, at times ambiguous and ultimately memorable horror film, based on a Daphne Du Maurier short story.

Travelling to Venice, the wife encounters a psychic who tells her that their daughter is “happy”. The husband is initially skeptical but thereafter a series of mysterious events occur, drawing the couple on a search through the maze of Venice’s dark and dank alleyways searching for a hooded figure glimpsed in the distance, convinced it could be the spirit or embodiment of their daughter.

The atmosphere of creeping dread and putrescence, combined with the intensely erotic yet strangely sad lovemaking of the couple, and the horrifying climax evolve with an almost tragic inevitability.

Yet Director Roeg still manages to defy expectations through his ability to build suspense through seemingly disconnected details and vignettes, and then avoiding neat resolutions or overt explanations which would otherwise make the film seem contrived or too preconceived.

Above all, it is a hauntingly effective dissertation on loss, grief and the influence such tragedies have upon the rationality of the human mind.

The Wicker Man,

A devoutly Christian policeman, Sgt. Howie (Edward Woodward), is lured to an isolated Scottish island community, “Summerisle”, which is steeped in ancient ritual and superstition.

It becomes increasingly apparent that the island is rife with the influence of a pagan cult, whose dark and terrifying secret becomes eventually apparent to the unsuspecting police officer.

The film, directed by Robin Hardy, effectively critiques the conflict between fundamental Christianty and paganism, while at the same time exploring the sometimes erotic and often bizarre natures of these individuals within this insular society.

While the merits of ‘The Wicker Man’ are actively debated by cinema critics, it is a true cult film which has a devoted following which should encourage those looking for an evocative and incisive foray into the macabre.

Seven Beauties,

Controversial, yet vividly surrealistic seriocomedy by Lina Wertmuller, features a masterful performance by Giancarlo Giannini as a small time hustler, Pasqualino Farfuso, who makes his living from the proceeds of the prostitution of his seven sisters.

Found guilty of murder, he feigns insanity and then escapes by joining the army, only to desert and eventually become an inmate in a Nazi concentration camp.

Pasqualino must overcome his massive ego, his misplaced sense of pride, and his overblown machismo to survive at all costs, eventually including the sacrifice of any and all human dignity in the degrading seduction of his captor.

Alternating wildly from moments of gentle, picaresque comedy to high farce, from elements of extreme horror to grotesque satire to intensely sad irony, this film runs the gamut of emotions yet manages to remain mordantly observant, without losing sight of the serious nature of the underlying themes of survival, complicity and cowardice, and the Holocaust subject matter it so graphically depicts.

- Honorable Mention:

The Train, Fail Safe, The Manchurian Candidate, Ace in the Hole, Odd Man Out, The Killing, The Wrong Man, The Killers (1946), Charlie Varrick, Friends of Eddie Coyle, The Long Good Friday, Mona Lisa, Prince of the City, Road to Perdition, Mosquito Coast, Southern Comfort, Bad Day at Black Rock, The Parallax View, The Year of Living Dangerously, Under Fire, The Quiet American, Medium Cool, Blue Collar, The Last Detail, Sling Blade, The River’s Edge, The Year My Voice Broke, Heavenly Creatures, I Walked with a Zombie, Cat People, Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1956), The Sweet Smell of Success, The Ladykillers (1955), Being There, The Freshman, After Hours, Me and Orson Welles, Melvin and Howard, Broadway Danny Rose, What About Bob?, Mad Dog and Glory, Last Temptation of Christ, The Chimes at Midnight (Falstaff), Othello (1952), Glory, Bite the Bullet, Danton, The Man Who Would Be King, An Actor’s Revenge, Red Sorghum, The Chant of Jimmy Blacksmith, Hester Street, The Dead, Bound for Glory, Once Upon a Time in America, Ragtime, Fitzcarraldo, El Norte, The Shining, Midnight Run, Eastern Promises, High and Low, The New World, Picnic at Hanging Rock.

- Strong Critical Successes Still Lacking Mainstream Recognition:

Atlantic City, Days of Heaven, The Conversation, Mephisto, Five Easy Pieces, Hud, Touch of Evil, The Sacrifice, The Spirit of the Beehive, Tree of Life, The Tin Drum, Reds, Killing Fields, The Last Picture Show, The Enigma of Kaspar Hauser, Mean Streets, My Life as a Dog, Jesus of Montreal, Fargo, Richard III (1995), Knife in the Water, Breaker Morant, Zodiac, The Thin Blue Line, Barry Lyndon, Wings of Desire.

![tucker-the-man-and-his-dream[1]](https://1984redux.files.wordpress.com/2012/07/tucker-the-man-and-his-dream1.jpg?w=382&h=215)

![hope-and-glory[1]](https://1984redux.files.wordpress.com/2012/07/hope-and-glory1.png?w=381&h=214)

![images[6]](https://1984redux.files.wordpress.com/2012/07/images6.jpg?w=365&h=260)